-

A few years ago, I spent an afternoon with a friend's 6 year old and watched him figure out the basics of HTML in a few hours - an occurrence that was cool, but unremarkable - HTML is known to be quite accessible and has a pretty low learning curve.

-

Later that same day I was chatting with a fellow CTO about how difficult it was to hire good engineers for our startup, and how I was going about communicating to my non-technical co-founder - who was questioning our monthly tech spend - that "This is just what a good tech team costs". At the end of that day, I reflected on both of those conversations, and couldn't let go of an intuition that something didn't add up.

-

Our software - for the most part, was written with HTML - the language that a 6 year old was able to learn (the fundamentals of) in less than a day. And yet at our startup, we needed so much skill, experience and intelligence that we could only hire very specific, hard-to-find people, and had to spend seven figures per year to simply maintain and extend our software. And we weren't even a SaaS company!

-

Now, of course there's more to production software than a 6 year old's "Hello World" website, but given the overlap in raw materials this didn't make sense to me.

-

As I've thought about this over time and run experiments with my team and with friends learning to code, I've concluded that no - there's not enough of a gap in difficulty should to warrant such an extreme difference in cost, skill and experience. And that there must be something else at play.

-

Death by a thousand tiny cuts

-

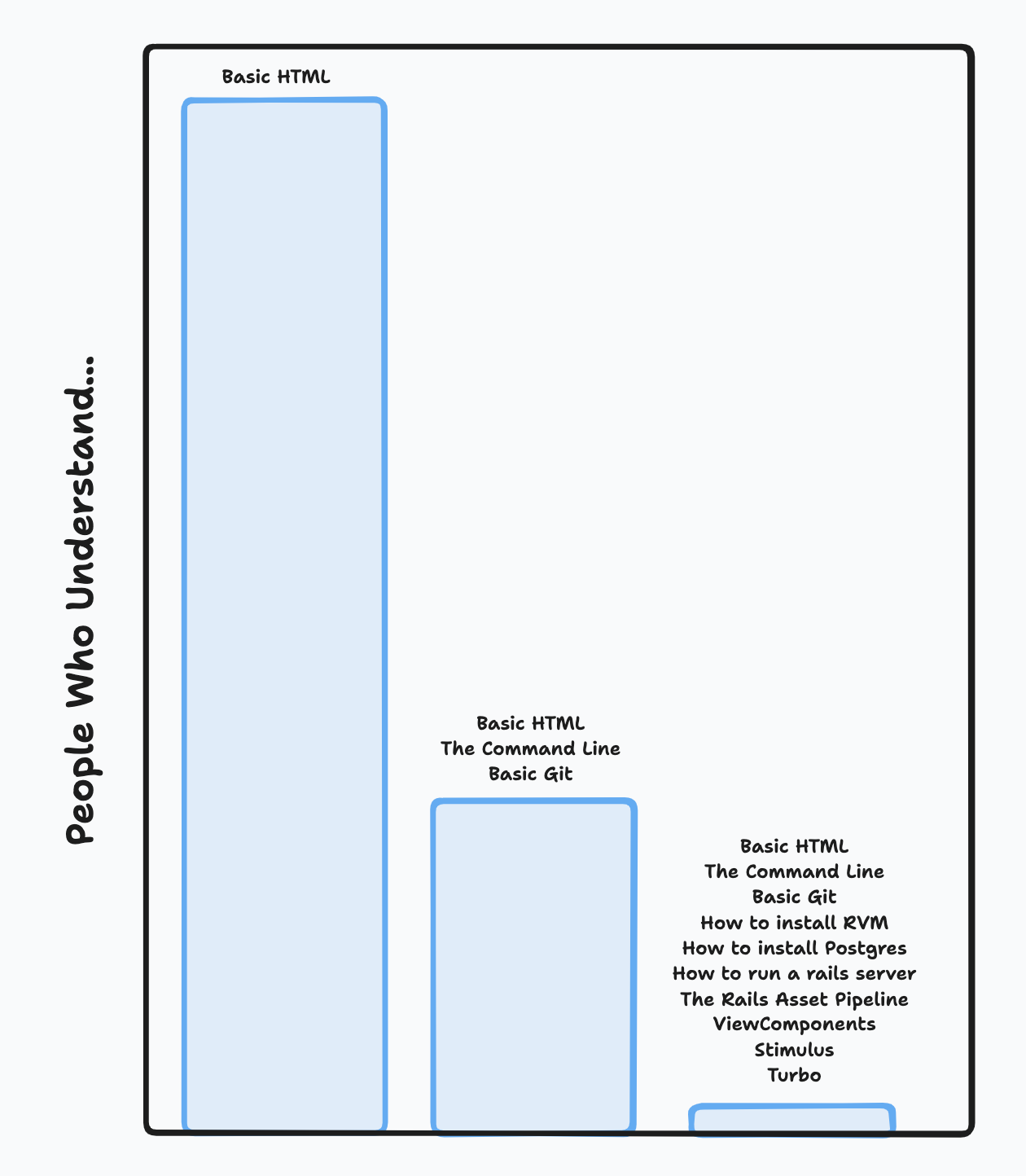

I've continuously been shocked at what people with little to no experience are capable of when you teach them one or two concepts (html tags, properties), and let them leave the harder stuff (environment setup, git, compilation, deployment) til later.

-

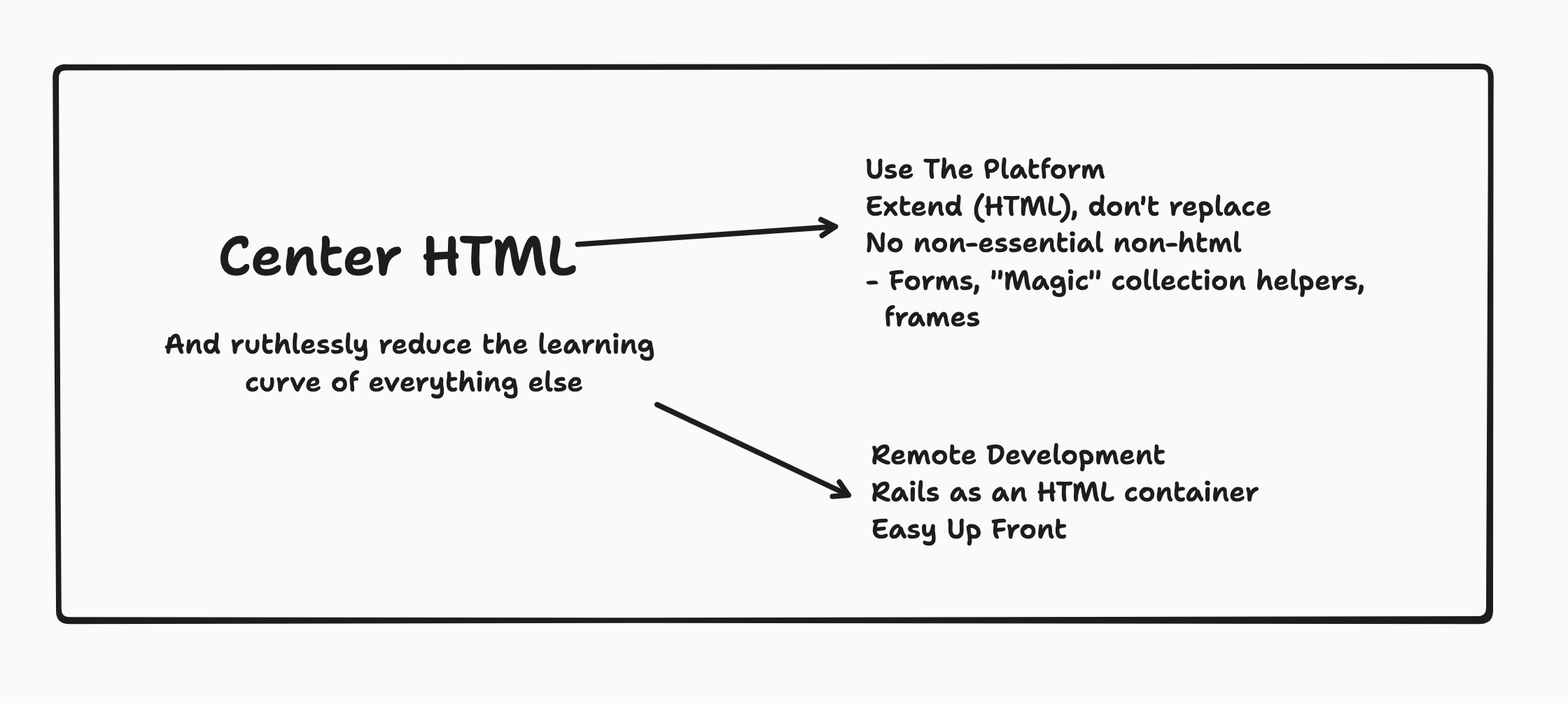

The line-of-thought I've arrived at is pretty simple: If the "learn-ability" of a codebase rises in step with each new concept added, then we should start with a few very simple concepts (html tags and properties), defer introducing more difficult concepts (and skills) until later, and not add new concepts to our codebase that will reduce it's learn-ability unless absolutely necessary. The easiest way to describe this underlying philosophy/rationale for how we now approach writing code is this.

-

-

I'll zoom in on Part 3 later -it's where most of the juice is in terms of how the principle is applied in practice, but first I want to address the obvious objection to thinking about codebases in this way.

-

Novice Friendliness doesn't just benefit Novices

-

Having run these ideas by quite a few people, by far the most common rebuttal is "Why the hell would we 'dumb down' our codebase instead of hiring people who are good enough and experienced enough to work with it?".

-

There are several good answers to this, but the most unexpected one is that by approaching things in this way, we not only ended up with codebases that less experienced developers could get up to speed with quickly, we also ended up increasing the output of the more experienced members of the team. It turns out that removing obfuscation layers and concepts that added marginal utility, we also reduced the amount of working memory needed to both build new features and debug existing ones.

-

Our codebase is maybe 20% more verbose than a typical Rails codebase, but what it lacks in "pretty-ness", it makes up for in understandability.

-

-

What the hell does "Center HTML" mean?

-

I first learned about the principle of Locality of behaviour from the folks at HTMX. It states that "The behaviour of a unit of code should be as obvious as possible by looking only at that unit of code". It runs contrary to many long-accepted best practices (DRY, Separation of Concerns), and yet - when applied to html - it results in code that - while more verbose - is also much more understandable and modifiable than code that strictly follows the Separation of Concerns principle.

-

Rails as an HTML container

-

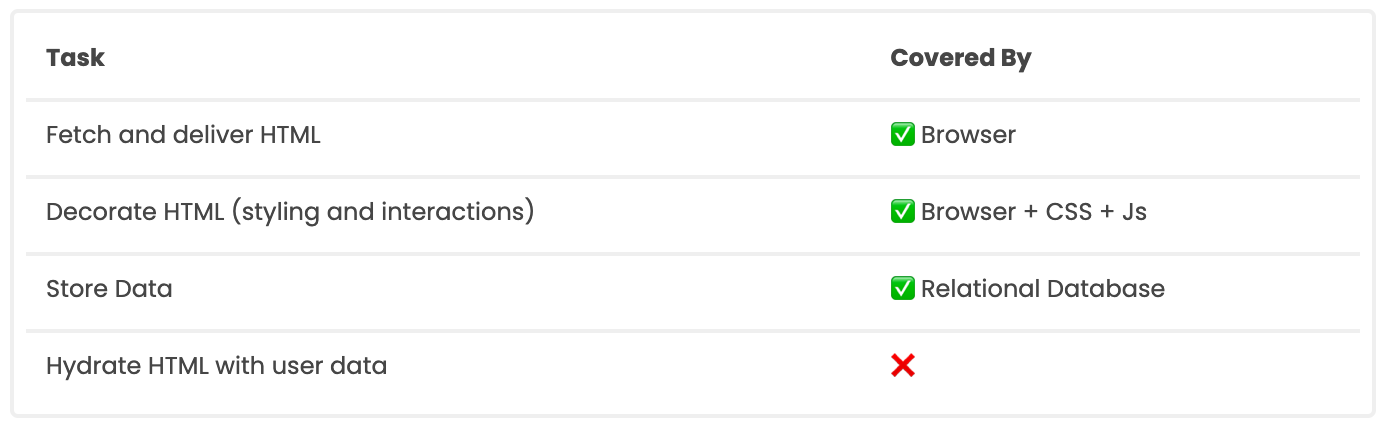

Web apps are built primarily around HTML. Browsers are designed to fetch and render HTML, and do it very well. Additionally, relational databases have been around for a long time and do their job - storing data - very well.

-

So without Rails, we already have out-of-the-box solutions for storing data, and for delivering HTML. What we don't have is a way to combine them both - to hydrate the HTML with specific data based on what user is requesting it.

-

-

As I've thought about this over the last few years, my frame has switched from "Rails is a large framework for building complex web apps, whose libraries and patterns (hotwire, stimulus, turbo, service objects, etc. etc.) need to be studied and learned", to "Rails is a way to access a collection of utilities that make it easier to work with HTML

-

I've written about some of the more specific ways we use Rails here: Friendly Rails Guidelines.

-

Diagram

-

-

Tony Ennis